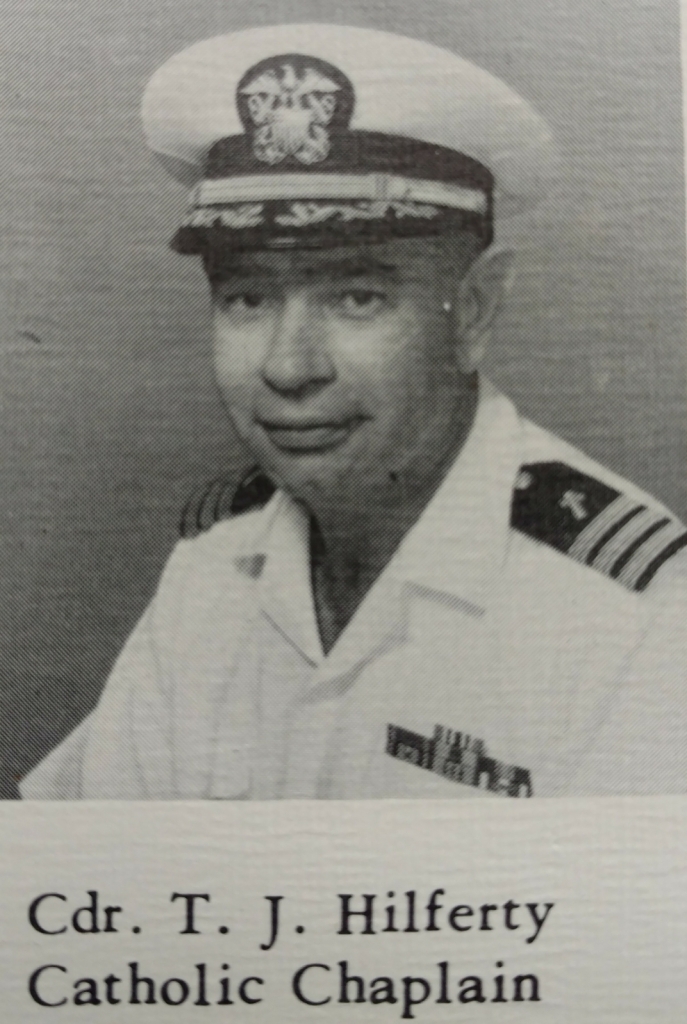

Was it unexpectedly shrewd Archdiocesan administration or divine providence that sent Father Hilferty to Saint Francis de Sales in 1977 for his first assignment as a pastor?

He was modest about his qualifications. He would tell parishioners that this belated first pastor assignment, at age 49, was not due to a late vocation – he was ordained back in 1952 — but because he enlisted as a Navy Chaplain in 1957 and stayed in the military for twenty years “until somebody noticed and sent me home.” But that unique experience made him peculiarly suited to the needs of the changing parish when a Ninth Pastor was required. And he was already familiar with the place, since his father and grandfather had both been buried from SFDS.

What was significant about Father Hilferty’s work as a Navy Chaplain? An initial trawl through newspaper databases finds him presiding periodically at weddings and giving speeches at local high schools, usually near the Naval Base in Newport, RI – work that seems routine. However, these moments turn out to have been the calm breaks between active postings. A deeper dive finds clues that he steered through some interesting times: between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis, the July 1962 Sunday Supplement for the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo noted that “After a year at Guantanamo Bay Lt. Thomas J. Hilferty is leaving for Naval Air Station, Washington, D.C. The much-traveled Father has served in the east and west – Japan to Gitmo…” And in June 1965, as the Vietnam war expanded, the Chief of Naval Operations and the Chief of Chaplains appointed Lieutenant Commander Thomas Hilferty as Navy Chaplain in Saigon.

Chaplain Hilferty’s initial posting to the Saigon military base first connected him with the Vietnamese community. According to the History of the Chaplain Corps, in addition to supervising religious services and counseling personnel on the base, an important function of the military chaplains was distributing humanitarian aid to civilians in South Vietnam. Chaplain Hilferty was also assigned to a Community Relations Committee, responsible for “formulating solutions to problems which arose out of the concentration of U.S. personnel in the Saigon-Cholon area.”

Housing issues would become his theme song. He soon saw how the large number of arriving Americans needing accommodations caused significant issues for the incumbent Vietnamese: American personnel were initially sequestered in secure but crowded compounds on the base, but as the military buildup began, “with few exceptions, every large hotel and apartment house, as well as many of the larger villas, was used for U.S. personnel. This deprived the Vietnamese nationals of many rooms and apartments and increased the housing problem caused by the influx into Saigon-Cholon of workers and refugees.” Additionally, many American servicemen preferred to rent their own properties outside the official housing compound to “live more privately, comfortably, and even luxuriously, and induced landlords to prefer Americans with their buying power to Vietnamese nationals who generally could not compete financially. The Vietnamese had to settle for substandard housing while American had two quarters: the authorized one and the one on the economy.” Chaplain Hilferty observed that “this situation is offensive to many Vietnamese who are not in the real estate business.” Understanding the issues on both sides, and learning to delicately negotiate workable solutions, foreshadowed his future efforts on this side of the ocean to resettle waves of Vietnamese refugees arriving in West Philadelphia, needing to be welcomed into scarce local accommodations.

When the humanitarian assistance program phased out on the Saigon base, as the war ramped up, Chaplain Hilferty was reassigned to become “the only navy chaplain ashore in II, III, and IV Tactical Zones in Vietnam.” A lonely job, this moved him through the jungle on swiftboats, right into the action. The History of the Chaplain Corps reports that “Captain Hilferty traveled up and down the coastline and along the rivers establishing contact with small, widely scattered units to which American personnel were attached…His efforts to provide religious coverage for personnel of sixteen widely scattered bases represented the beginning of what was to become the Saigon-based chaplains’ circuit riding ministry.” As the solitary chaplain, his efforts were ecumenical, ministering to everyone in need. Eventually, a protestant chaplain was assigned to help and they alternated routes: one going north; the other south; then reversed.

Getting places was half the fun. Chaplain Hilferty’s eventual replacement on the circuit would later report “Ordinary travel by road is almost non-existent due to the ever-present possibility of ambush by the Viet Cong…Fortunately, air travel came to my rescue…This padre became a familiar and welcome sight to the crewmen of AIR COFAT (Naval air support). As one of the pilots once said, ‘Padre, it’s always good to see you aboard. We feel like you’re a third engine. Start praying.’ Unscheduled hops on Army choppers, Air Force planes, and water transport were part of the routine. To make a one-day visit to a detachment usually involved at least a full day spent in traveling to and from the unit.” Chaplains had to cultivate patience and flexibility, and remain unflappable in any situation. This would be an asset for Father Hilferty, when he arrived at SFDS, where memories of a rectory home invasion and gunpoint robbery in 1972 had left behind a deep residue of anxiety. Father Hilferty was unimpressed by tales of neighbourhood toughs, and, like the recent popular meme, his example to the parish was ever to keep calm and carry on.

His successor in Vietnam wrote about the physical and psychological drain on chaplains who “had to experience death many times over,” administering last rites to mangled corpses and comforting the terrified, mortally injured, and bereaved. Their ministry was raw and the needs they addressed were immediate and traumatic. This was much different from the squabbling at SFDS over the modern Venturi altar and the new rituals of Vatican II, which had taken up so much parish energy. Under Father Hilferty, the parish refocused to embrace the incoming Vietnamese – and all the other refugees and immigrants from faraway places who came to the parish and school at the time, fleeing horrors and arriving destitute. Sisters Constance and Jeannette nurtured war-traumatized children and evolved an award-winning school. Father Hilferty encouraged parish cooperation with representatives of other non-Catholic religious institutions in the neighborhood as they worked together to open a credit union to solve a local banking crisis, and looked for ways to deal with other pressing local issues.

Father Hilferty was appointed Director of the Black Diaconate for the Archdiocese in 1978, while at SFDS. In 1989, Monsignor Hilferty moved on from SFDS to become the regional Vicar of Philadelphia-South, at St. Carthage. After several other assignments, he became Pastor, then Pastor Emeritus of Queen of Peace Church, Ardsley, Pa. He died in 2008.